Why Did Ishiba Release a “Personal Message” on WWII Right Before Stepping Down?

and Can It Push Japan to Squarely Confront Its Past?

*The Chinese version of this article is here.

On 21 October, TAKAICHI Sanae was appointed the new prime minister of Japan, becoming the first female leader of the country. The prospect of her assuming this position was once doubted due to one of the biggest political turmoils in recent years. Yet little attention has been paid to her predecessor’s important decision, made before he left the office.

(Takaichi Sanae, being appointed as the Prime Minister of Japan)

(Source: the official Instagram of the Prime Minister’s Office of Japan)

On 10 October, the then Prime Minister ISHIBA Shigeru released a “Prime Minister’s Personal Message” (内閣総理大臣所感) to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II.

(Ishiba Shigeru at the press conference on 10 October)

(Source: Mainichi Shimbun)

The past has always been an aporia for postwar Japan. The scars it left, both internally and externally, in the war that ended 80 years ago are still, in some ways, aching.

In order to address historical issues, especially calls from other countries urging Japan to fulfil its wartime responsibilities, the Japanese government has released statements in the name of the prime minister every decade since 1995, the year marking the 50th anniversary of WWII’s end. So far, three such postwar statements have been issued: the Murayama Statement in 1995, the Koizumi Statement in 2005 and the Abe Statement in 2015. It is therefore natural that public attention focused on whether the government would issue a new statement (namely, the “Ishiba Statement”) in 2025, the 80th year since the end of the war.

However, the document released by Ishiba is unusual compared to his predecessors’.

First, it was not released on 15 August – the day remembered as “End of the War Memorial Day” in Japan – nor on any date close to it, unlike all previous postwar prime ministerial statements. On 7 September, Ishiba had announced his intention to resign as both prime minister and president of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, after facing internal pressure to step down following the party’s defeat in the Upper House election in July. Since then, his government had become a “lame duck,” especially after Takaichi was elected as the new LDP leader on 4 October. Moreover, amidst an unprecedentedly uncertain political landscape – following the end of the long-standing ruling coalition between the LDP and Komeito – Ishiba’s message on WWII was less likely to gather sufficient attention.

Second, this is merely a “personal message” by the prime minister, in sharp contrast to previous postwar governmental statements, which were all issued under cabinet consensus and thus carried greater official weight. Given these circumstances, it remains unclear how influential Prime Minister Ishiba’s Personal Message will be in the future.

Table of Contents

What is the PM Postwar Statement?

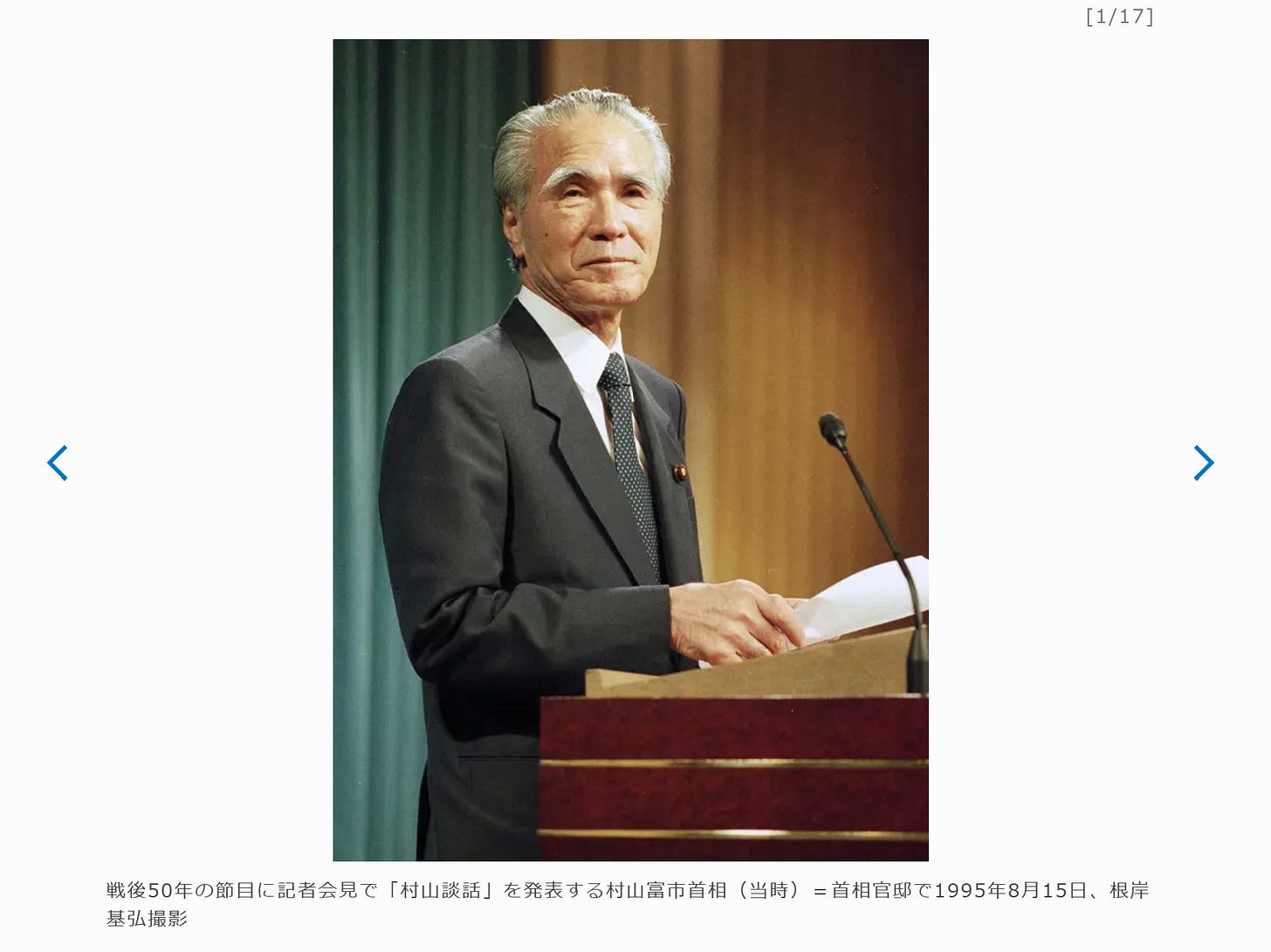

The first postwar prime ministerial statement was issued in 1995, the 50th year after the end of WWII, under the then Prime Minister MURAYAMA Tomiichi (who has recently passed away on 17 October). The 1990s were a period when history had re-emerged as unresolved issues in East Asia again. After a former comfort woman in Korea came out for the first time in August, 1991, multiple lawsuits were subsequently brought against the Japanese government throughout the 1990s. Murayama chose to issue a governmental statement to address Japan’s historical responsibility; it is also said that Murayama, as the first Socialist Party leader to take office, has a strong personal conviction on the importance of confronting historical issues. The Murayama Statement was released on 15th August, 1995, with Cabinet consensus, including ministers from the LDP. It openly expressed Japan’s “deep remorse” and “heartfelt apology” for its past “colonial rule and aggression”, undertaken under a “mistaken national policy”, which caused “tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations”.

(Murayama Tomiichi at the press conference on 15 August 1995)

(Source: Mainichi Shimbun)

The Koizumi Statement, delivered on 15th August 2005 to mark the 60th anniversary of the war’s end, basically followed Murayama’s line, amidst the political frenzy of a snap general election that began on 8 August (which is a crucial factor that this statement is scarcely known). Although KOIZUMI Junichiro has often been criticised for his repeated visits to Yasukuni Shrine during his premiership, he reiterated “deep remorse and heartfelt apology” regarding past “colonial rule and aggression” and the “tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations” it inflicted, while omitting certain expressions as “a mistaken national policy”. A distinct feature of the Koizumi Statement was its emphasis on Japan’s six decades of “manifesting its remorse on the war through actions”, highlighting contributions to global peace and prosperity through official development assistance and participation in UN peacekeeping operations. It was also significant as the first such postwar statement issued by a LDP prime minister.

(Abe Shinzo at the press conference on 14 August 2015)

(Source: Sankei Shimbun)

The Abe Statement, released on 14th August 2015, was prepared under complex circumstances, and still has a significant impact on today’s political discourse on historical issues. The then Prime Minister ABE Shinzo and his Cabinet did a thorough preparation and coordination. An expert committee called “The Conference on Japan’s Vision for the 21st Century” was set up in February, and submitted its final report to the Cabinet on 6th August1. The statement drew heavily on this report, lending it an element of institutional legitimacy. Abe, known for questioning the historical views expressed in the Murayama Statement and his willingness to rewrite it2, was closely watched for whether he would include the four key terms: “aggression”, “colonial rule,” “remorse” and “apology”3. In the end, however, he makes it explicit that his government succeeds all previous postwar statements. In the Abe Statement, “deep remorse and heartfelt apology” for Japan’s “actions during the war” is stated; expressions such as “colonial rule” and “aggression” were included, albeit in a context not particularly referring to Japan’s past deeds. Distinctive characteristics of the Abe Statement include its length, its broad reference to modern world history; for instance, it mentions Western colonial expansion, and depicts some of Japan’s modern achievements positively, such as Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War and the sense of encouragement it gave to Asian people. Another distinct feature is its attempt to conclude Japan’s apology, writing “we must not let our children, grandchildren, and even further generations to come, who have nothing to do with that war, be predestined to apologise”. While there are criticisms of both the Abe Statement and the person who released it, it also widely gathers positive comments. Prof HOSOYA Yuichi, a scholar of international politics at Keio University, commented that “the Abe Statement’s contents are what can be broadly accepted by Japanese citizens” and that its historical perspective aligns with “the international community’s understanding of the last great war”4.

The Tug-of-War behind the “Failed” Ishiba Statement

While governmental postwar statements are not required by law or regulation, they have somehow become a political custom after being issued in three consecutive decades. It was therefore natural that attention turned to whether a Postwar 80th-Year Statement would be released. In the end, however, no such “Ishiba Statement” based on a cabinet resolution was released.

The main reason was strong opposition from both within and outside the LDP. Many argued that the Abe Statement had already concluded Japan’s apology and reflection on the war, and that no further statement is necessary. For instance, KOBAYASHI Takayuki, widely regarded as a promising young conservative voice within the party, remarked on 4th February that “the Abe Statement gained a wide range of support from Japanese people. (…) I am concerned that a statement to break the unity of Japanese people might be released”5. Similar opinions were expressed outside the party as well. Prof KITAOKA Shinichi, vice-chair of the expert committee that drafted the Abe Statement, claimed that the 70th-anniversary postwar statement had already put a punctuation mark to Japan’s “diplomacy of apology”, and they should “let sleeping dogs lie”6.

(Kobayashi Takayuki)

(Source: Sankei Shimbun)

Another likely reason was the difficulty of coordinating a new postwar statement amid numerous domestic and international challenges, including inflation – particularly the surge in rice prices – and Trump’s tariff war. The situation worsened after the LDP’s defeat in the Upper House election in late July, which triggered calls within the party for Ishiba’s resignation. As a result, the prime minister’s team abandoned plans to establish an advisory body for the statement and chose to avoid releasing a document that could intensify backlash inside the party7.

Yet even after announcing his stepping down, Ishiba did not abandon the idea of issuing a message on wartime history. In late September, during the LDP leadership election, it was reported that Ishiba planned to release a “personal message”, not passed by the cabinet meeting, after the new party president was elected but before he formally steps down as prime minister. The news sparked controversy. Three of five candidates – Takaichi, Motegi and Kobayashi – expressed opposition to releasing any war-related document under in the prime minister’s name, while Koizumi and Hayashi – both serving ministers in Ishiba’s Cabinet – showed their understanding.

In early October, the release date was officially set for 10 October. The newly elected LDP President Takaichi strongly objected to Ishiba’s plan. Several LDP lawmakers also expressed disapproval before the release8, but it did not stop Ishiba. On 10 October – coinciding with the date when a major turning point in Japanese politics happened – Ishiba released his personal message.

What Does Ishiba Say in His Personal Message?

Ishiba’s “Personal Message” on wartime history differs significantly from previous prime ministers’ statements. Its reflective tone on the complex reasons behind Japan’s misguided choices suggests that it is more of an inward-looking message than an outward-facing statement laden with diplomatic considerations. Its length is also notable – almost twice as long as the Abe Statement.

(Ishiba Shigeru at the press conference on 10 October)

(Source: Nihon Keizai Shimbun)

In the opening, Ishiba explicitly clarifies both the continuity and the distinctions between his message and earlier prime ministerial statements. He declares not only that he inherits all of them, but also that he seeks to complement their shortcomings. Ishiba argues that all three preceding statements failed to explain why Japan could not avoid entering war, citing a passage from the Abe Statement: “(Japan) attempted to overcome its diplomatic and economic deadlock through the use of force. Its domestic political system could not serve as a brake to stop such attempts.”

This point reveals the central theme of Ishiba’s message: why Japan’s political system was unable to prevent itself from going to war. He highlights that Japan embarked on a reckless war even though certain governmental and military institutions – such as the “Institute for Total War Studies” (総力戦研究所), established in 1940 – had already foreseen the country’s inevitable defeat. Ishiba writes, “On the year marking the 80th anniversary of the postwar era, I would like to contemplate this question together with distinguished citizens.”

The written message consists of six sections: flaws in the Constitution of the Empire of Japan, the responsibilities of the government, the Diet, and the media, flawed intelligence, and insights for the present day.

The first section points out numerous flaws in the prewar constitution, including the absence of a proper system integrating the government and military, the severely limited powers of the prime minister and the lack of civilian control (so-called “inalienable independence of the Supreme Command”). Under this system, the government had to rely on the elder statesmen who had participated in the Meiji Restoration and the Boshin Civil War to restrain the military. Yet this personal system of deterrence gradually lost effectiveness as those figures passed away.

Subsequently, the military expanded its influence by invoking the “independence of supreme command.” The second section describes how the government gradually lost its authority over the army.

The Diet was no exception. Ishiba cites the “anti-military speech” delivered by lawmaker SAITO Takao on 2 February 1940, in which Saito criticised the prolongation of the ongoing war and questioned its purpose. The army’s strong backlash led the Diet to expel him by an overwhelming majority. Even today, two-thirds of the session’s records remain undisclosed9.During the war, military expenditures were largely treated as special accounts and thus escaped sufficient parliamentary scrutiny. Many politicians were also assassinated by the military, as seen in the May 15 and February 26 incidents.

(Saito Takao)

(Source: Asahi Shimbun)

One of the sections that gathers the most attention is on the media’s complicity. Ishiba notes that while the media had been critical of Japan’s external expansion in the 1920s, its stance shifted dramatically after the Mukden Incident, as war coverage turned out to be profitable. This sensational reporting became a driving force behind the rise of nationalism. Censorship introduced in 1937 further worsened the situation, leaving citizens exposed only to pro-war voices.

Ishiba also points out that defective intelligence contributed to the government’s flawed understanding of the international situation at the time.

The “Insights for Today” section is the lengthiest part of Ishiba’s message. After acknowledging improvements such as the establishment of civilian control, the expanded powers of the prime minister and the creation of the National Security Council – which integrates diplomacy and defence, Ishiba argues that the government must have the capacity and expertise to oversee the Self-Defense Forces. It also bears the responsibility to coordinate across departments and to make sound, long-term judgements for the benefit of all citizens. Ishiba repeatedly underscores the vital roles of both the Diet and the media.

He asserts that the Diet must properly monitor the government’s actions by exercising its constitutional powers. “Politics must never succumb to short-term public opinion or pursue self-serving, vote-winning policies that undermine the national interest,” he warns.

From Ishiba’s perspective, the existence of a “healthy public sphere”, supported by a responsible media, is indispensable. “We must avoid excessive commercialism and must never tolerate narrow-minded nationalism, discrimination, or xenophobia,” he writes. Referring to the assassination of Abe Shinzo, he adds, “Political violence and discriminatory speech that threaten free expression can never be condoned.”

Ishiba emphasises the importance of “learning from history” as the moral foundation of all actors. He argues that “what is essential above all is the courage and integrity to face the past squarely, a genuine liberalism – the humility to listen to others – and a sound, resilient democracy.” Citing Winston Churchill, he observes that democracy, as an imperfect system, is prone to mistakes and therefore requires both cost and time to function effectively. Hence, “we must always remain humble before history and engrave its lessons deeply in our hearts.” Democracy, as a fragile system, can only be sustained by a shared understanding of these lessons among all actors – “the government, the Diet, the armed forces and the media.”

Given today’s geopolitical tensions, Ishiba concludes that “the importance of learning from history must be reaffirmed precisely now, when Japan faces one of the most severe and complex security environments of the postwar era.” His message ends with a vow to work together with Japanese citizens to ensure that such tragedies are never repeated.

The subsequent Q&A session at the press conference was also insightful. During the one-and-a-half-hour-long event, Ishiba answered all questions from journalists. When asked about criticism from the “so-called conservative group”, he reiterated that his message maintains continuity with the Abe Statement, while addressing questions it had raised but left unresolved. He also drew on personal experiences – such as his past visit to Singapore and his experience of being pointed out his ignorance of Japan’s wartime atrocities there by Lee Kuan Yew.

Ishiba made clear his awareness of today’s global crises. He mentioned deepening divisions in America and Europe, citing Aristotle’s argument that the weakening of the middle class breeds social division and conflict. He also referred to the newly elected LDP president, Takaichi Sanae, expressing hope that under her leadership, the LDP and Japanese politics as a whole will firmly reject xenophobic sentiment and unjust discrimination.

Throughout, Ishiba repeatedly acknowledged the shame he felt upon realising his own lack of historical awareness, citing the books and perspectives that had shaped his reflections. He expressed his commitment to continual learning and self-examination numerous times.

How Should Ishiba’s Message Be Read?

Ishiba’s Personal Message has elicited diverse responses regarding both its content and its nature. While it has been largely praised for its critical analysis of prewar Japan’s systemic flaws and its meaningful insights for the present, it has also been criticised for its incomplete analysis and its ambiguous status as a document.

Many commentators have commended the message’s reflections on the domestic factors that led Japan to war. Prof ICHINOSE Toshiya, a modern Japanese history scholar at Saitama University, notes that the message is concrete in its discussion of internal governance issue, and successfully incorporates insights from academic studies10. TAMAKI Yuichiro – the leader of the opposition Democratic Party For the People (DPFP), who previously expressed reservations about the prospect of an “Ishiba Statement” – commented that it holds certain significance for identifying systemic problems that led Japan into war11. Prof ICHIHARA Maiko, a scholar of international politics at Hitotsubashi University, praises its strong advocacy of democracy, describing it as “an excellent message demonstrating Ishiba’s deep commitment to democracy” and a meaningful message today from a leader of one of the major democratic states12. Interestingly, some conservative voices have expressed relief that it does not revise the Abe Statement’s resolve to prevent future generations from being forced to continue apologising – exemplified by Sankei Shimbun’s opinion column. NAGASHIMA Akihisa, a ruling LDP lawmaker, expresses his positive views on Ishiba’s message and notes that “it does not rewrite the Abe Statement (…) and has no content undermining the national interests” on his official X.

(Nagashima Akihisa)

(Source: Sankei Shimbun)

However, Ishiba’s message also contains significant shortcomings. Its omission of references to “aggression” and “colonial rule” has also drawn criticism from the leaders of the opposition Social Democratic Party and the Japanese Communist Party13. TSUJITA Masanori, an independent writer mainly specialising in Japan’s modern history, criticises its vague references to “the war” and its failure to acknowledge Japan’s wartime perpetrations, particularly in Asia. In a podcast, Tsujita notes that the message entirely overlooks Japan’s war crim, and fails to specify which “war” it addresses – for instance, the “Institute for Total War Studies” mentioned in the opening was established for the war against the United States, while lawmaker Saito’s “Anti-Military Speech” was delivered during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Indeed, the message does not refer to “China” and other Asian countries (aside from a brief mention of Ishiba’s visit to the Philippines during his term), which makes it puzzling that wars against the United States and China are conflated under the vague expression “the last great war.” Overall, Tsujita concludes that it amounts to a document that merely “lists historical facts”.

Diplomatic and international perspectives are also notably absent. Prof Ichinose points out that “it would have been better if the message discussed what lessons Japan could learn from its relationships with the U.S. and China at the time, in light of today’s international relations”14. The conservative Sankei Shimbun touches on this point from another angle, referring to the alleged mistreatment of Japanese nationals in China and the Western powers’ colonial domination of non-white peoples.

Another major controversy concerns the decision to release a “personal message” under the prime minister’s name. NISHIDA Shoji, a ruling LDP lawmaker, argues that it is meaningless to issue such a document after Ishiba’s resignation had been confirmed, calling it merely a gesture born of his desire to leave his mark in history – a view echoed by other conservatives15. FUJITA Fumitake, leader of the opposition Japan Innovation Party, questions the value of releasing a document whose official status remains unclear in the absence of cabinet approval. Prof KONO Yuri, a historian of Japanese political thought at Hosei University, contends that it is inappropriate that an outgoing prime minister to issue a personal message that could easily be mistaken abroad for an official government position16. Tsujita similarly argues that Ishiba’s message is insufficient as a political statement because it fails to indicate concretely what actions he intends to take as a politician; he concludes that Ishiba’s message is incomplete, whether we read it as a critical essay or a political statement.

Asahi Shimbun shows a different view. In its opinion column, it asserts that this message holds certain significance as a document issued by a sitting prime minister, but warns that it should not remain “empty words without actions”, urging Ishiba to continue engaging with society and politics even after stepping down.

What Can Ishiba’s Personal Message Bring to Japan’s Historical Reflection

As discussed above, Ishiba’s personal message attempts to confront the question of why Japan went down the wrong path and ended up starting wars, though it remains flawed and has drawn criticism both within and outside his party.

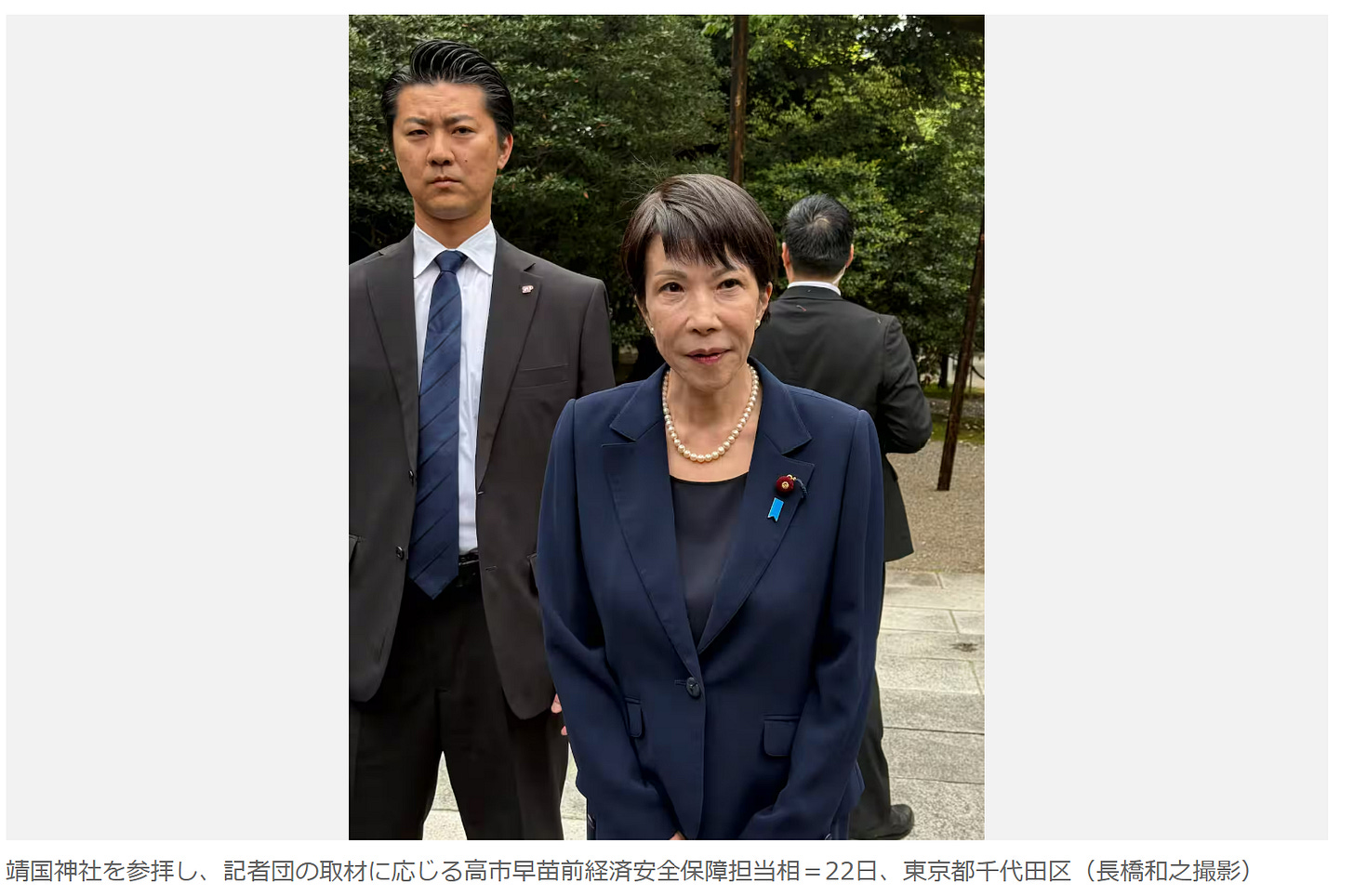

Contemporary Japan faces formidable challenges to conducting a sincere historical reflection: the rise of xenophobic sentiment, the spread of populist rhetoric among politicians, and increasingly severe geopolitical tensions. The new prime minister, Takaichi, who succeeded Ishiba on 21 October, is known for her right-wing stance on historical issues, exemplified by her repeated visits to the Yasukuni Shrine. While Takaichi has not clearly expressed her views on Ishiba’s message, it is unclear whether she will even read it. The only comment she has made so far was, “I have no idea what it says,” on 10 October17.

(Takaichi Sanae, visiting Yasukuni Shrine in Spring this year)

(Source:Sankei Shimbun)

On the other hand, Ishiba’s message has the potential to offer a model for a new kind of historical reflection. Many conservatives argue that Japan’s responsibility to apologise was concluded by the Abe Statement. In a sense, Ishiba turned this argument to his advantage: while affirming continuity with previous prime ministers’ statements, including Abe’s, he shifted the focus entirely to Japan’s internal institutional flaws. In this way, the “closure” of formal apologies in response to external pressure might liberate Japan from repeating formulaic diplomatic expressions and instead encourage a more genuine, inward-looking reflection on its past.

However, this mode of reflection also risks enabling narratives that shift blame onto others, as seen in Sankei Shimbun’s opinion and in the historical displays at the Yasukuni Shrine’s museum (Yushu-kan).

The true impact of Ishiba’s prime ministerial personal message remains to be seen. Yet the series of events surrounding it – and the divided voices it provoked – reveal that Japan’s past still casts a spell on the nation.

References

Abe Shinzo 安倍 晋三, Yamatani Eriko 山谷 えり子. “<緊急対談>保守はこの試練に耐えられるか [Conversation: Can Conservatives Endure This Challenge?].” Seiron 正論, 02 2009: 50-59.

Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞. “(社説)首相80年所感 言いっ放しで済ますな [Opinion: PM’s Postwar 80th-Year Message Should Not Be Just Empty Words without Actions].” Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞. 13 10 2025. https://digital.asahi.com/articles/DA3S16322073.html (accessed 10 19, 2025).

—. “高市総裁「内容わかりません」 石破首相の戦後80年所感に否定的 [LDP President Takaichi Shows Negative Reaction to PM Ishiba’s Postwar 80th-Year Message].” Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞. 10 10 2025. 高市総裁「内容わかりません」 石破首相の戦後80年所感に否定的 (accessed 10 20, 2025).

—. “石破首相、戦後80年の所感発表 「なぜ戦争を…」個人の立場で検証 [The Announcement of Postwar 80th-Year Message by PM Ishiba].” Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞. 10 10 2025. https://digital.asahi.com/articles/ASTBB2P89TBBUTFK016M.html?iref=commentator_detail_article (accessed 10 19, 2025).

—. “石破首相の戦後80年見解 高市氏支持の保守系議員らが発表中止要請 [PM Ishiba’s Postwar 80th-Year Message: Conservative MPs supporting Takaichi are Requesting to Cancel].” Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞. 08 10 2025. https://digital.asahi.com/articles/ASTB83J1RTB8UTFK00TM.html?iref=pc_ss_date_article (accessed 10 20, 2025).

—. “戦後80年文書なぜ見送り? 石破首相に意欲も党内に保守派の反発 [Why Was Postwar 80th-Year Document Cancelled?: While PM Ishiba is Willing, the Conservative Voices inside the Party is Opposing ].” Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞. 02 08 2025. https://digital.asahi.com/member_scrapbook/detail.html?aid=AST821QXRT82UTFK02QM&cflag=0&psub=5&page=2&limit=20&sort=regtime.desc (accessed 10 20, 2025).

Cabinet Decision. “Statement by Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 15 08 2005. https://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/announce/2005/8/0815.html (accessed 09 15, 2025).

—. “Statement by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.” Prime Minster of Japan and His Cabinet. 14 08 2015. https://japan.kantei.go.jp/97_abe/statement/201508/0814statement.html (accessed 09 15, 2025).

—. “Statement by Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama “On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the war’s end”.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 15 08 1995. https://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/press/pm/murayama/9508.html (accessed 09 15, 2025).

Government PR Online 政府広報オンライン. “21世紀構想懇談会による報告書の提出-平成27年8月6日 [The Submission of the Report by the Conference on Japan’s Vision for the 21st Century on 6th August, 2015].” Government PR Online 政府広報オンライン. 06 08 2015. https://www.gov-online.go.jp/prg/prg12179.html (accessed 09 15, 2025).

Isaji Ken 伊佐治 健. “【証言】戦後70年・安倍談話 「戦争を正当化しない」日本人の“義務”と中国の“膨張主義” 東大・北岡名誉教授 [The Postwar 70th-Year Abe Statement: “We Should not Justfiy the Past War”, the “Obligation” of Japanese and “Expansionism” of China by Prof Kitaoka].” Nippon Television News. 19 01 2025. https://news.ntv.co.jp/category/politics/68dddd38039442738e254e2b58d70772?p=6 (accessed 09 09, 2025).

Kyodo News 共同通信. “野党、所感内容に評価分かれる 「意義ある」「反省ない」 [Divided Responses to the Message among Opposition Parties].” Tokyo Shimbun 東京新聞. 10 10 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20251010172751/https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/441865 (accessed 10 19, 2025).

Mainichi Shimbun 毎日新聞. “「志は感動した」が現実に悲しさも 歴史学者が感じた戦後80年所感 [How a Historian Sees the Postwar 80th-Year Message].” Mainichi Shimbun 毎日新聞. 11 10 2025. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20251011/k00/00m/010/137000c (accessed 10 19, 2025).

Oda Takashi 小田 尚 . “「戦後70年談話」を巡る攻防 /安倍氏は「侵略」を認めた [How the Postwar 70th-Year Statement was Made: and How Mr Abe admitted “Aggression”].” Japan National Press Club. 01 2021. https://www.jnpc.or.jp/journal/interviews/35191 (accessed 09 09, 2025).

Prime Minister’s Office of Japan. “(内閣総理大臣所感)戦後80年に寄せて [Prime Minister’s Personal Message: On 80th Year after the End of the War].” Prime Minister’s Office of Japan. 10 10 2025. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/content/20251010shokan.pdf (accessed 10 20, 2025).

—. “石破内閣総理大臣記者会見 [The Press Conference by PM Ishiba].” Prime Minister’s Office of Japan. 10 10 2025. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/103/statement/2025/1010kaiken.html (accessed 10 20, 2025).

Sankei Shimbun 産経新聞. “<主張>戦後80年所感 平板なリポートのようだ [Opinion: PM Personal Message on Postwar 80th-Year is like a Mediocre Paper].” Sankei Shimbun 産経新聞. 11 10 2025. https://www.sankei.com/article/20251011-Y6DSBVFHEVLOTBMJ57AE64WVDY/ (accessed 10 20, 2025).

Shoji Junichiro 庄司 潤一郎 . “「戦後 70 年談話」の新視点―歴史観を中心として― [New Perspectives in the Postwar 70th-Year Statement: On its Historical Views].” NIDS Commentary Vol. 10, 7th July, 2015: 1-4.

Sports Hochi スポーツ報知. “石破茂首相の「戦後80周年見解」に保守派論客が猛批判「イタチの最後…」「資格がない」「許せない!」…正義のミカタ [Strong Backlashes from the Conservative to PM Ishiba’s Postwar 80th-Year Personal Message].” Sports Hochi スポーツ報知. 11 10 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20251011033239/https://hochi.news/articles/20251011-OHT1T51034.html?page=1 (accessed 10 19, 2025).

The Political News Department of Jiji News 時事通信政治部. “「反軍演説」議事録の復活検討 石破首相指示、与野党協議へ [PM Ishiba Requests the Coordination between the Ruling and Opposition Parties to Consider the Fully Disclosure of the Meeting Record of “Anti-Army Speech”].” Jiji.com. 01 10 2025. https://www.jiji.com/jc/article?k=2025100100948&g=pol (accessed 10 18, 2025).

—. “「反軍演説」議事録の復活提案 立民 [CDP Suggesting the Fully Disclosure of the Meeting Record of “Anti-Military Speech”].” Jiji.com. 15 10 2015. https://www.jiji.com/jc/article?k=2025101500952&g=pol (accessed 10 18, 2025).

Tokyo Shimbun 東京新聞. “「迫力不足の最後っ屁」 石破首相「戦後80年所感」に社民・福島瑞穂党首が不満 「自民党内への配慮としか…」 [The Reaction to PM Ishiba’s Postwar 80th-Year Personal Message by the Socialist Democratic Party’s Head Fukushima Mizuho].” Tokyo Shimbun 東京新聞. 10 10 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20251011014600/https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/441833 (accessed 10 19, 2025).

(Government PR Online 政府広報オンライン 2015)

For instance, in his conversation with another politician, which is published in Seiron, a conservative magazine, Abe expressed his complaint that the Murayama Statement became “a litmus test” of historical views for each cabinet, and his willingness to release a more “balanced” PM statement in his first term. (Abe Shinzo 安倍 晋三, Yamatani Eriko 山谷 えり子 2009)

(Oda Takashi 小田 尚 2021)

(Shoji Junichiro 庄司 潤一郎 7th July, 2015)

(Sankei Shimbun 産経新聞 05.02.2025)

(Isaji Ken 伊佐治 健 2025)

(Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞 02.08.2025)

(Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞 08.10.2025)

As a side note, at the beginning of October, Ishiba asked the LDP’s board to consider the full disclosure of the meeting records (The Political News Department of Jiji News 時事通信政治部 2025). The coordination between the ruling and opposition parties are underway, as of 15 October. (The Political News Department of Jiji News 時事通信政治部 2025)

(Mainichi Shimbun 毎日新聞 11.10.2025)

(Kyodo News 共同通信 2025)

(Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞 10.10.2025)

(Kyodo News 共同通信 2025) (Tokyo Shimbun 東京新聞 2025)

(Mainichi Shimbun 毎日新聞 2025)

(Sports Hochi スポーツ報知 2025)

(Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞 10.10.2025)

(Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞 10.10.2025)